The COVID-19 outbreak has compelled us all to take shelter in the virtual world to escape from the dark reality. It is not wrong to say that internet has become an essential or a necessity in today’s times. Be it binge-watching shows, vocalizing our voices against government policies, keeping ourselves updated with the various developments around the world or even attending online classes, internet has surely helped us in keeping our sanity intact during these testing times. While more and more people are getting comfortable in this digital space, states are encountering new challenges towards ensuring the safety and security of its citizens. This apprehension has once again brought to light the concept of ‘cyber sovereignty’.

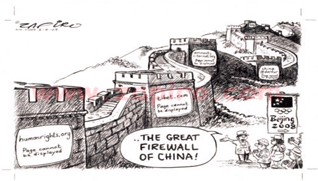

Cyber sovereignty refers to the assertion of state control over technology-linked flows, whereby the state both defines and guarantees rights in the digital realm. This narrative of sovereignty in cyberspace was introduced by China with a two-fold purpose. Firstly, to ban unwanted interference in a country’s ‘information space’ (in other words to justify the infamous Great Firewall of China).

Secondly, to prevent cyber hegemony. Even though this was a fairly comprehensive notion, it was shunned by most democratic countries of the world when authoritarian countries like China and Russia used it to justify unacceptable practices including censorship of political opinion, tight control of internet gateways etc. Today scandals like Cambridge Analytica, manipulation of public dialogue and rise in online surveillance have compelled all the countries to revisit this concept in order to solve issues like content regulation and anonymity while assuring core values including openness and accessibility.

India’s decision of banning 59 Chinese applications within the country is a one of kind move to embrace this concept by giving it a new definition. While giving China a taste of its own medicine, the government invoked this power under section 69 A of the IT Act to preserve the national sovereignty and security of the nation.

Chinese apps including TikTok, UC Browser, WeChat that were accused of breaching user data privacy have recently been asked questions by the union government as part of an investigation into the matter. These include questions on censorship of content, lobbying influencers, privacy policies of the company etc. While this move was welcomed by the whole nation in the backdrop of the Galwan attack, the constitutionality of the geoblock is yet to be reviewed given the insufficient information communicated via the Press Information Bureau notification.

While this appears to be a purely retaliatory technique, it has significant consequences on the multifaceted Indian population (almost 100 million active users) who had regular access to platforms like TikTok. As rights under the Constitution must be viewed as a network of interconnected freedoms, it is the state’s duty to manage its cyber security and privacy while ensuring that key fundamental rights like freedom of expression and access to internet should not be undermined in the process.

To determine whether this state action is justified it must satisfy the following conditions laid down in Modern Dental College v. the State of MP namely,

- Perseus a Legitimate Interest

- Is rationale to achieve the object sought

- Is necessary and not an excessive measure

- Is proportionate in restricting the right

Further, the recent ban on the websites leading a campaign against the draft EIA 2020 is another alarming instance towards the growing internet censorship in the country.

All these vulnerabilities are stemming from the lack of a robust data protection framework in the country.

Although the concept of cyber sovereignty must develop according to the need of the hour, one must not forget that balancing state autonomy with constitutional safeguards will go a long way in countering any trends towards executive discretion.

This post was written by Muskan, IIIrd year